It’s 4:45 p.m. on opening night of the spring exhibition at the Picker Art Gallery. Scott Lewis kneels on the floor with a paintbrush, dabbing at scuff marks. Last-minute touch-ups completed, he grabs a dolly laden with easels, blocks, and tools and scuttles for the gallery exit. At 4:55 p.m., he and the curatorial assistant remove the last bits of equipment and race everything upstairs into storage before the first guests arrive at 5 p.m.

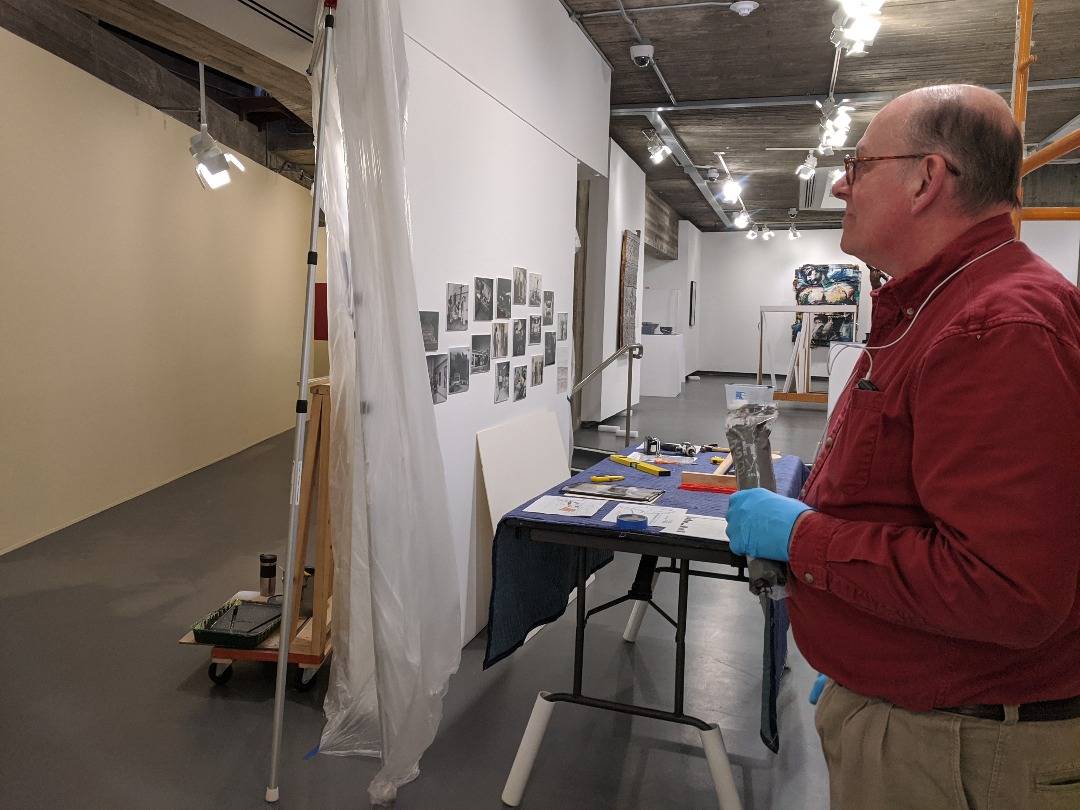

Lewis is a preparator. He works behind the scenes to install exhibitions at Colgate’s Picker Art Gallery and Longyear Museum of Anthropology. “I’ve been in this line of work since 1978,” he says. “It combines the skills of a carpenter, a metal worker, a painter, and a designer. I get up close and personal with objects that most people have to stay three steps back from. It’s a real privilege.”

Creating an exhibition is a meticulous and collaborative process. Curators craft the vision and message of the show, and choose objects to display. A collections manager or registrar is in charge of the physical well-being of the objects and determines whether the object is too delicate for exhibition.

The preparator determines that the objects will fit in the physical space, paints the walls in the gallery, procures framing materials, builds the frames, and constructs mounts for objects that will be displayed in cases.

“Exhibition installation is a collective effort,” says Lewis. “The whole staff gets together to talk it over, and people present ideas from different points of view. Being open to that creativity makes it fun.”

Once the content and message of the show are determined Lewis moves into the gallery. “We lay out the artwork on blocks in the gallery to get an idea of how it will look, and then make changes to the plan based on that,” says Lewis.

To hang objects on the gallery walls, Lewis starts with a tape measure and a center line 58 inches from the gallery floor. For a more complicated array of pieces, he might use a laser level. He favors picture hangers with two or three nails for extra security.

Some pieces are secured to the wall to prevent an accidental bump from causing a catastrophe. “Even though people aren’t supposed to touch the artwork, gallery openings can be crowded events. We pay attention to the traffic flow through the gallery and guard against accidents. Whether we’re showing a work that is by an unknown maker or something touched by the hands of a master, we treat everything with the same care.”

After the works of art are hung or mounted, Lewis applies the explanatory labels and vinyl wall text. The last step is the lighting. There are specific light levels considered safe for different objects. “Works on paper — such as drawings — are very fragile,” says Lewis. “Anytime they are exposed to light the pigments fade.” He uses a light meter to measure the illumination and then adjusts the light levels using small shades he makes out of window screen.

Then, it’s time for those touch-ups. “When you go to a show on opening day, watch out for wet paint,” he jokes.

For more information on the Picker Art Gallery’s latest exhibition, an exploration of the Picker’s collection of 17th century Dutch and Flemish works, please visit Original Materials II: The Picker Art Gallery and the Building of a Collection.