For my AMS project I wanted to investigate storytelling in other countries. I found that some of the most important national narratives are found in memorials that commemorate important events and collective tragedies, which are defining moments in a country’s history. As an English major, I am interested in text-based storytelling, but I also appreciate the power of art, photographs, statues, and other modes of representation. I had the privilege to travel to four different countries with my study abroad program, Semester at Sea. While in Japan, Vietnam, Mauritius, and South Africa, I used my AMS funding to visit important sites such as commemorative museums and engage in interpersonal exchange where possible. Here is a brief summary of my key findings in each country.

Hawaii, USA:

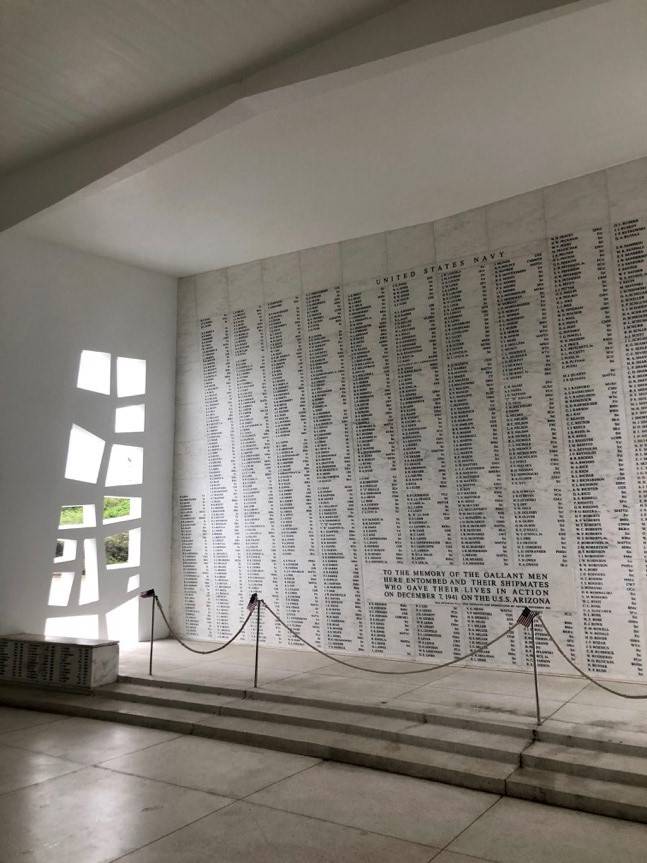

My first stop in this journey was the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor. I got to visit the national memorial, which is part of a larger complex including the U.S.S. Utah and other historical artifacts. We watched an educational video about World War II and the events of December 7th, 1941 when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and over a thousand sailors and marines lost their lives. The U.S.S. Arizona memorial is constructed over the remains of the ship itself. It is accessible only by Navy boat and the National Park Service sells tickets to control crowding. An educational video and an audio tour complemented the storytelling of the monument itself. All other information was transmitted through visual art and engravings. The memorial itself was a silent space out of respect for those who died there. For me, the most impactful part was hearing the voice of a survivor (part of the audio tour) describe the experience of the Arizona sinking while standing above its remains. Oil leaks from the sunken battleship and the rainbow slick visible on the surface of the water, which is referred to as the tears of the Arizona.

Japan

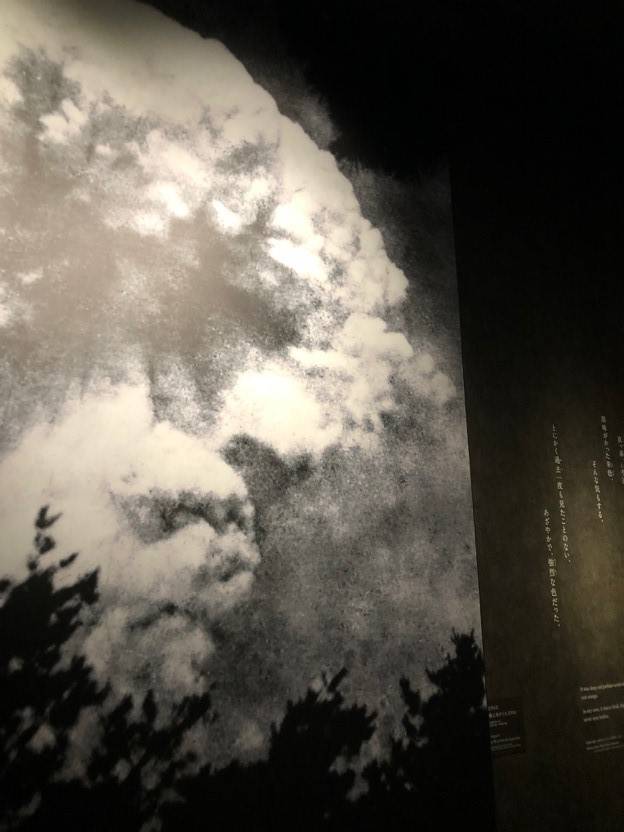

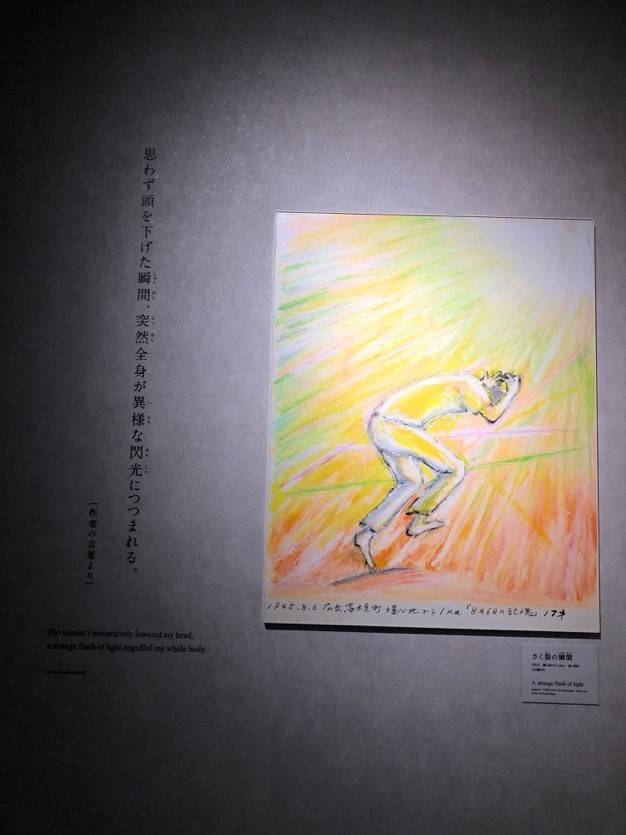

In Japan, I took the bullet train from Kobe to Hiroshima. Here I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial and Atomic Bomb Museum, commemorating the events of August 6th, 1945 when the U.S. dropped a nuclear weapon on the city of Hiroshima during World War II. This was an incredibly powerful place to visit. The museum itself is full of visual and written stories and the surrounding Peace Park is equally moving. Thousands of photographs, maps, historical artifacts, statues, building remains, and interactive art tell the story of the A-bomb tragedy. In addition, each artifact (shoes, toys, clothing, etc.) is accompanied by a short story of the individual or family to whom that artifact belonged. These stories were the most influential to me because they made history personal and produced strong feelings of empathy. I also got to hear directly from a second-generation survivor who told her family’s story through an emotional PowerPoint presentation. She emphasized that she tells her story not to place blame but to ensure that this kind of devastation is never repeated again.

Vietnam

In Vietnam, I knew I needed to visit the War Remnants Museum, which commemorates the Vietnam War, as we know it. Similar to the A-bomb museum in Hiroshima, the War Remnants Museum uses a lot of different mediums to tell the stories of a tragedy. What stood out to me here was the important role of newspaper clippings and press photography. An entire room was dedicated to media coverage of the war. Inside each exhibit, photographs and quoted interviews told of personal experiences and lesser-known stories. Furthermore, visual art was a significant component of the museum as well. I think this medium is a good complement to text-based artifacts because it is accessible to many audiences and can communicate a certain perspective that may be difficult to capture in words. There is a lot of historical art and propaganda pieces both promoting and opposing the war, as well as contemporary art created by second and third-generation victims of Agent Orange. The children’s art was the most emotionally moving to me personally. This showed me how simple images can contain complex, layered stories and a range of emotions.

Mauritius

In Mauritius, a small island nation off the coast of Africa, I decided to visit the Museum of Sugar since sugarcane is important to the country’s history and present reality. I learned about the agricultural and ethnological history of Mauritius in my classes and wanted to see how the museum told these stories in the country itself. When I arrived in Mauritius, the first thing I noticed was how green it is everywhere. In fact, sugarcane dominates most the island’s land space. Wherever you drive, you pass fields of sugarcane. It was interesting to compare the historical narrative presented in the museum to what I had learned in class. The museum sometimes glossed over the violence that surrounds this agricultural product. For instance, a video exhibit highlighted one man who was a formerly enslaved laborer, but later opened his own confectionary business. I felt that this singular success story diverted attention away from sugarcane’s legacy of widespread oppression and violence, from which many people never rebounded. In contrast, I thought the museum succeeded in capturing sugarcane’s complicated history in Mauritius with respect to foreign intervention. This involved the Portuguese, Dutch, French, and enslaved people brought from Africa, and was not a straightforward story to tell. Moreover, I found the museum’s use of technology very useful. They had an app with additional audio content and stories of individual laborers and plantation owners.

South Africa

In South Africa, the final country of my journey, I decided to visit Robben Island, an island near Cape Town where Nelson Mandela and many other prisoners (political and criminal) were kept from as early as the 1600s to the end of apartheid in 1996. I was interested in how people told the story of this places, especially since its historical narrative ended so recently. My visit consisted of a tour around the island by bus with a few stops, and a walking tour of the maximum-security prison led by a former political prisoner. During the first part, my tour guide told stories with the same detachment as anyone would who has not personally experienced something. He was able to convey meaning without getting visibly emotional. My second tour guide, who had spent nine years imprisoned on the island, had a different manner. He seemed restrained and conflicted about sharing his experiences with tourists, understandably so. It was easier for him to tell stories in a general sense rather than recall his personal experiences. Additionally, I thought it was important that he elaborated on the history of Robben Island by telling us his experiences of leaving and eventually returning. It was evident in our guide’s accounts and in the general feeling of the island that Robben Island’s story is ongoing and censorship is still in progress.