Why Gaeilge?

The Irish language, Gaeilge, is not spoken fluently by many. I started learning it about four years ago, and reactions from family and friends tended in the direction of expressing incredulity that the Irish language even existed. But it does — it is a strange, difficult, beautiful language, and one that I’ve grown passionate about since beginning to learn it. Initially, I started it as a challenge at the beginning of quarantine in 2020. This led to a fascination with Irish history and politics, and how the language and culture have evolved throughout the island’s history. For this project, I was able to travel to Belfast, Dublin, and Galway to examine firsthand how Gaeilge fits into Irish society.

Belfast: History and Politics

For a city still technically situated within the United Kingdom, Belfast is jarringly aware of its Irish heritage. Signs of the conflict between Britain and Ireland are everywhere — you can’t walk through the city without seeing the face of an Irish Republican or a Unionist filling up an entire wall, often accompanied by assault weapons, staring you down as you get your morning tea. In some neighborhoods, street signs are listed in both Irish and English. In others, the British flag is flown proudly. In most cases, these neighborhoods are separated by formidable walls — sometimes lined with barbed wire or spikes and extending more than 20 feet into the disputed Irish sky.

The walls mentioned above, dividing “Catholic” from “Protestant” are, ironically, called “peace walls.” They began as a way for the British military to kill two birds with one stone — they were able to both somewhat control sectarian violence (even the strongest arms strain to vault a Molotov cocktail over eight meters of concrete) and cordon off neighborhoods for easier surveillance. Though the walls were supposed to have been taken down in the early 2000s in the aftermath of the Troubles, many remain to this day, and neighborhoods are still divided along cultural and socioeconomic lines. Some of the gates still open and close every morning and night to prevent fights from breaking out among “youngsters” who like to organize fights (in the words of our taxi driver).

Today, the walls serve as an outlet for political expression for Belfast inhabitants. Beyond street signs and flags, the manner in which this wall is decorated is an excellent indicator of what neighborhood you’re in. Between traditionally Irish and British neighborhoods, the political slant of the murals changes — one street corner was particularly stark, transitioning from an arm with a Palestinian flag grasping an arm with an Irish flag on one side of the block to a mural in support of Israel on the other.

Beyond the stark divisions made evident by the murals, they are also intriguing because of their global awareness. The wall is an outlet for political expression, and Belfast residents have taken to making statements about world events that they feel reflect their situation. From Palestine to Kurdistan to the United States to South Africa, the murals are bound by a sense of international solidarity.

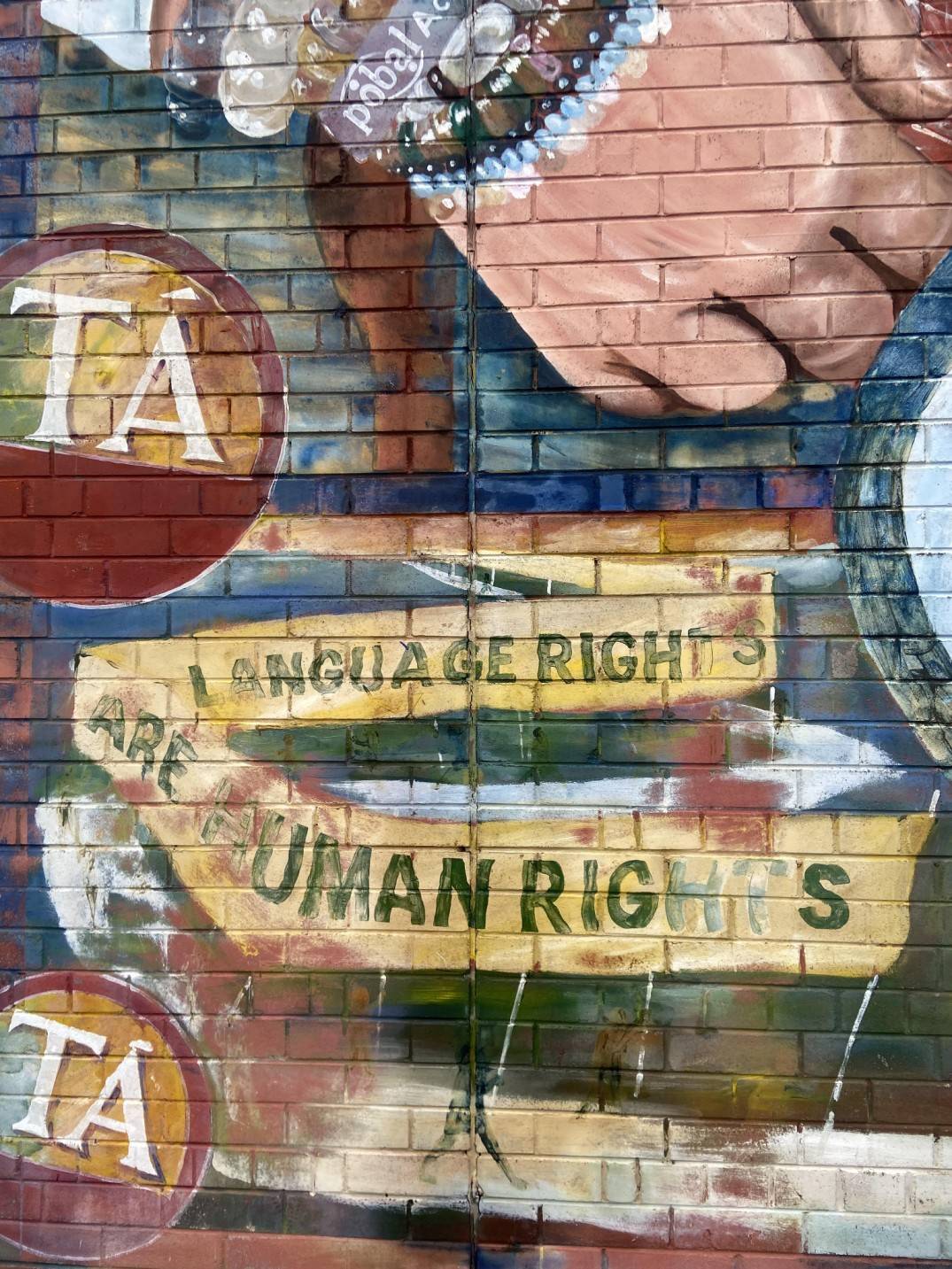

An issue closer to home, the Irish language, Gaeilge, is a recurring theme in the murals. It appears throughout Irish Catholic quarters, where people marching for their right to their language are shown alongside phrases like “language rights are human rights” and “is Gaeil sinne” (“we are Irish.”)

I toured the murals in a black taxi, a popular activity for tourists in Belfast looking to understand the political and social history of the city. Stephen, our guide, was a wealth of information. He expressed frustration over the degree of control Britain had over Belfast, making comments like “Brexit was a scam” and “If the Tory party told the unionists to stick their hand into the fire, they’d ask how far to stick it in.” From his perspective, what’s causing issues today is the refusal on the part of Unionists to compromise — he said that “when you live in a place that’s virtually 50/50, there has to be compromise,” and Unionists refuse to accept that they are not the majority. According to Stephen, there’s legislation that was just passed that will put Irish on all street signs. This is already a practice in Wales and Scotland for their respective languages, but Unionists in Northern Ireland resisted this for decades because they wanted to dispel any connections to Ireland. English was their unifying factor with the United Kingdom and allowed them to assimilate more into British culture. Stephen said that he took Irish for a year and wasn’t a fan, but asserted that about 20% of the population speaks the language, and not just Catholics.

Dublin and Galway: Street Signs and Pubs

In Dublin, Gaeilge is much more common. As soon as we stepped off the train, signs were in Irish first, then English. In a city that doesn’t boast a large Irish-speaking population, this seems like a political statement — a prioritization of cultural heritage over the language imposed on them by colonizers. One local we spoke to claimed that “Irish is everywhere, but in place names,” and that the Irish people “know French better than we know Irish,” going on to call attention to the difficulty of the language and the poor quality of instruction in schools. From his perspective, Irish wasn’t a worthwhile endeavor, as it is not useful in daily life. He viewed it as a sign of cultural heritage, but not really a working language.

This seemed to be a common perspective — we spoke to one man who ran a stall at a market and was even more critical of the school system. His philosophy seemed to be that knowing the language was respectable, but that it is so difficult and detached from everyday life that it shouldn’t be required, especially since it isn’t taught very well. In his words, “You shouldn’t shove it down people's throats, but if you’re clever, good for you.” He also expressed prejudices concerning which Irish people spoke the language, implying that only ethnically Irish people learned the language and making a joke about another seller not speaking the language predicated on the fact that she was Black. I didn’t encounter another instance of such explicit exclusion of certain groups from speaking Gaeilge, though the Irish-speaking spaces I encountered throughout my trip were patronized predominantly by white people, which is unsurprising due to the demographics of the country but may indicate a deeper-rooted issue. At Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, the woman working the counter distributing maps and audio tour guides had similar critiques of the Irish language education provided in schools. She explained that you learn it in schools from the age of 5 until you’re 18, but that it’s not taught very well. She also pointed out that you lose it over time since areas where it’s spoken casually are few and far between. At her desk, there were pamphlets and audio guides in Gaeilge — she explained this, saying that they are required by the government to offer things in Gaeilge, so tourist spots always have these options, even though most Irish people aren’t patrons. On the day we visited, just one person had taken an audio guide in Gaeilge.

This negative view of the Irish language stemming from poor education is a topic of concern for organizations that are striving to popularize the language and bring it back to a working status. We spoke to a man working the counter at Siopa Leabhar, a book shop owned by Conradh na Gaeilge, one such organization. He says that despite this sort of contempt for the language among older generations, he’s seen an increase in interest over the last few years. In his view, older generations have a negative view of Gaeilge because it was taught like a school subject, including the corporal punishment that was legal in Irish schools until 1982. Now, however, he says it’s being taught like a language and a piece of cultural heritage. He’s seen interest in younger generations increasing, which he attributes to outreach programs becoming more effective. He said that he regularly saw kids enter the shop and sit in the chairs in the back and read books in Gaeilge.

From Dublin, we next traveled to Galway. Though Galway itself is a popular tourist destination, it is surrounded by more remote parts of the Emerald Isle. Located opposite Dublin, we crossed the island to get there, and, as we did, we witnessed a visible shift in culture. As we got further and further from Dublin, road signs exclusively in Irish became more and more common. I found this deeply interesting — the urban-ness of the area and the degree of Irish spoken seemed to be negatively correlated. The portrayal of Irish as a dead language is not truly accurate; I must admit, even as someone learning the language, I didn’t know what to expect once I got to the island. But from conversations with people in Ireland, I gleaned that the most fluent Irish communities are located in more rural areas of the country. While my transportation options were limited and I was mostly restricted to cities, I hope to make my way to a true Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking region) one day and experience a way of life dependent on the Irish language.

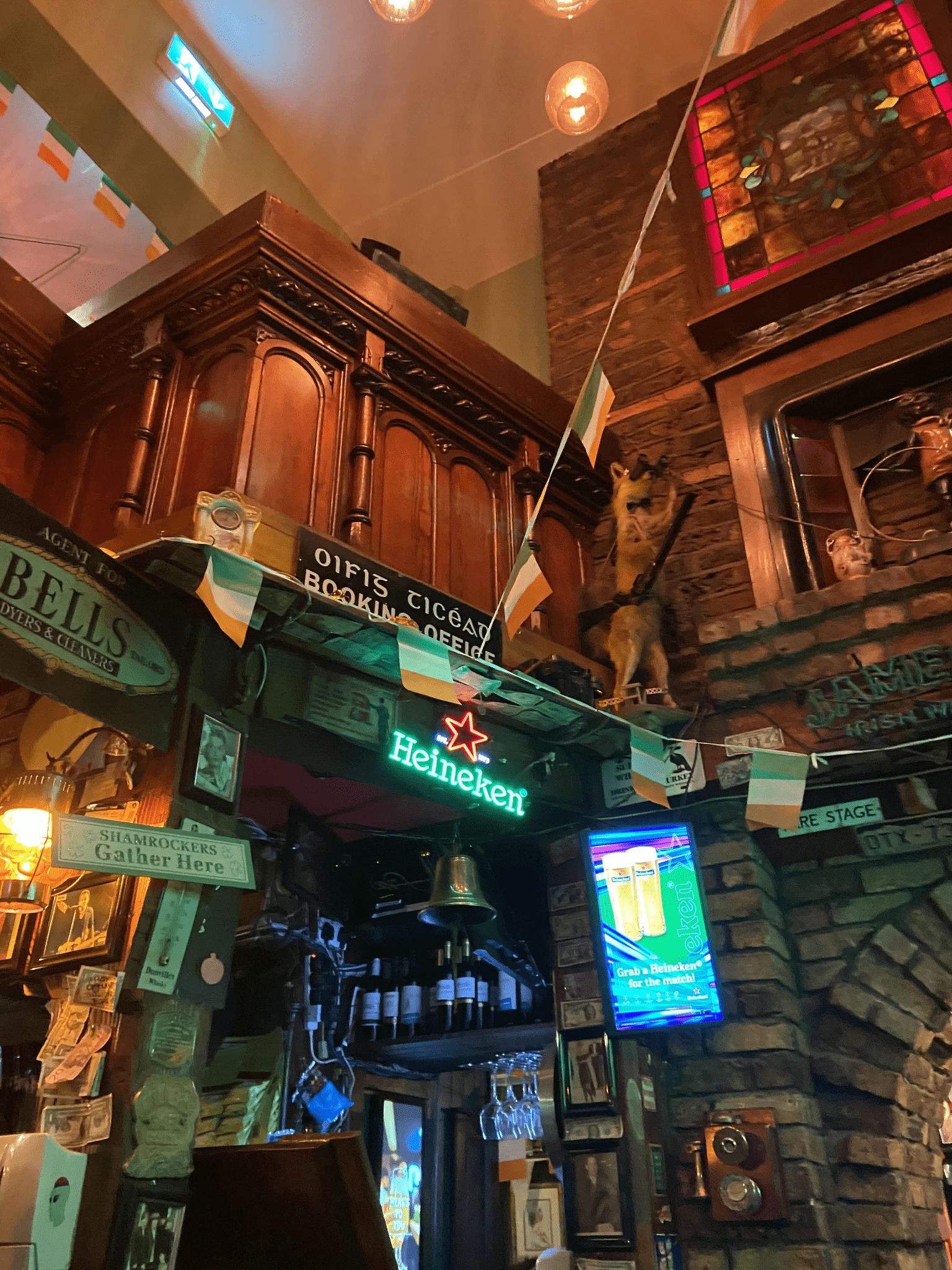

Pockets of Gaeilgeoiri (Irish speakers) in Dublin are numerous, however — while you do have to seek them out, they’re welcoming spaces and incredible opportunities to exist in a space where Gaeilge is the lingua franca. I found myself spending two nights at Pub Chonradh na Gaeilge, an Irish-speaking pub whose funds go to the organization Conradh na Gaeilge, whose goal is to bring Irish back to the status of a working language. It was particularly popular among young adults either attending or who had previously attended Irish-language schools throughout their primary and secondary education. Pub Chonradh na Gaeilge was an experience — the bartenders were open to talking to us once we expressed an interest in the Irish language and culture (and requested that they play “Come Out Ye Black and Tans”). Their opinions on Irish politics were strong, to say the least — one refused to refer to Northern Ireland as Northern Ireland, instead calling it “the north of Ireland,” driving home the point that the island was unified by a shared history and culture that no British intervention could dilute or overcome.

The Future of Gaeilge

What I witnessed in Ireland both confirmed and contradicted my expectations in different moments and social contexts. The overarching narrative is that the Irish language is dead, kept on life support by an educational system with a weak curriculum; while I did come across people who held this view and it’s undeniable that the majority of people speak little to none of the island’s original language, there is a rising interest in its preservation, particularly among youth. The characterization of the language as dead discounts the many rural areas where it’s still the lingua franca and the valiant efforts being made by organizations such as Conradh na Gaeilge to revive it in all parts of the nation. Ireland is an island rich with culture and political tension, and its troubled history has fractured its heritage; the Irish people, however you define them, have been left to do what they will with the pieces. From Belfast to Dublin to the green expanses between, you don’t have to look far before finding someone concerned to some extent with Gaeilge. How this piece fits into the ever-evolving puzzle of the Irish national identity has changed throughout the island’s history, and continues to mold itself to fit into society however it can, whether it’s radio stations or road signs or conversation. I feel lucky to have been able to witness firsthand the beauty of a space where people are fluent and comfortable with the language and hope that it finds its permanent place in Irish society.