Security is precarious when you come from the Global South. And Malcolm X was right when he quipped that “Mississippi is anywhere south of the Canadian border.” (422) Once, at a table in the Merrill House, it became clear to me that people from these ‘souths’ learn here and they work here too.

Indeed, for some, being employed at a predominantly wealthy institution does not ensure the financial security that many presume. My father retired when he was 70 years old. The day he retired, a Friday (he was insistent on completing a final cycle of the work week), I arrived home in Kingston, Jamaica, to spend the winter break. I had been only a few years at Colgate then — a young professor — too excited by the shine of a job, the wonderful and fearful little kingdom of the classroom, and all the many things to learn, to be tired in the ways I now know tired or in the way he must have felt at the end of his career.

A civil engineer by training, my father had done his part in building an independent Jamaica when he returned from school in London in the 1960s. But for most of the decades I’d known him, he was principally an entrepreneur. His latest and longest venture was growing and producing Blue Mountain Coffee. Blue Mountain Coffee then had many glorious years. But even Blue Mountain Coffee had no armature against a rapidly devaluing Jamaican dollar, praedial larceny, and a long-time business partner with long-time sticky fingers.

That evening in December 2007, he had left his emptied office with two boxes: one with a few wooden sculptures and small paintings; the other with a coffee mug, ceramic pencil holder, a clock, and some files. He said goodbye to his business of over three decades and entered retirement on the verge of financial ruin. No one else but him knew until we all knew because he had fallen apart under the weight of it all.

I won’t describe what followed in any detail, but I will say that the dynamics and rhythms of our lives changed. As quickly as a December break can become the middle of January, my life of parental and financial security fell away. I was fortunate for sure. I had many years of comfort and stability, and if things were falling apart at home, I was now grown with an education and a job; I was what old-time Caribbean people would term ‘past the worst.’ After all, I have known many students — mere teenagers — who sent their work-study earnings home and any cash from their aid packages to pay utility bills, fees for younger siblings, and keep food on the family table. This was not that, but it was something.

There is no high ground when your family is underwater

Early in 2022, I sat among peers in Merrill House, at a hushed table that would erupt now and again into bubbly laughter, sag with heavy sighs, or flash with ‘child, pleases’ and the watery sharp sound of suck teeth. It was at a faculty diversity council event, and we were filled with well-spiced food and good vibes. In the conversation that I remember, there were mostly Black women from across the campus.

What I had not known in the way I do now is how many colleagues at Colgate are like me. I think the best way to describe us is mostly Black and Hispanic, from the domestic United States and the Global South. Some have always done what they do now — support their families with regular financial contributions. For others like me, sending money home is a steady feature of their adult life. Whether our family’s needs have roots in generational poverty and inequality or the turbulent insecurities of the Global South, whatever the reason, we face familial needs that are persistent and acute.

The rapid devaluation of the currency in one’s home country could, in a year, disappear retirement savings meant for a decade. Even if a PhD (and a job!) is regular evidence of reaching a promised land, in post-Jim Crow America, the milk and honey aren’t so plentiful when your family is still wandering in the paycheck-to-paycheck wilderness. And what of war? The folks I am talking about take care of parents, siblings, and their siblings’ children. In addition to the regular things, there is sometimes a graduation, sometimes a funeral, and sometimes a promising young relative who wants to take a trip with their class. We are happy to do it, and we often wish the receivers would understand that we aren’t rich and that funding the regular maintenance, the gift, or the loan involves sacrifice. Anyone who knows some version of this story knows that there is no high ground when your family is underwater.

White Roger

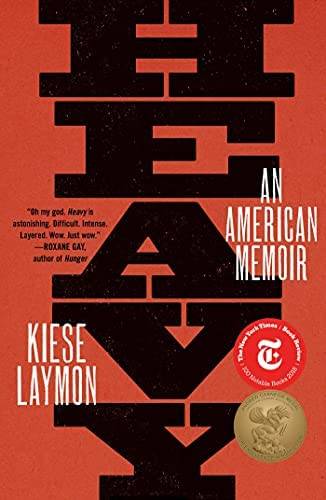

As we talked in hushes and splashes, I was reminded of Kiese Laymon’s memoir Heavy. When Laymon is an undergraduate at Millsaps College in Mississippi, writing establishment-provoking, anti-racist articles for the Millsaps paper, his mother’s former lover — the lawyer Malachi Hunter — stages an intervention intended to save Laymon from angry frat boys and the administration.

Hunter reasons that Laymon doesn’t have the resources to fight this American as-an-assault rifle fight; a fight that had already threatened his life. Hunter asked Laymon, “Who is the richest nigga you know?” When he answers that it is Hunter, Hunter seeks to prove that no matter how much money he makes, he can never be as rich as white Roger, another lawyer and friend of Laymon’s mother:

“Let’s say white Roger made three hundred thousand dollars, too. You following me? My three hundred thousand ain’t close to white Roger’s three hundred thousand. If I made that little three hundred thousand, I’m still the only nigga with money I know, you see? My girlfriend ain’t got no money… My mama and daddy ain’t got no money. My sisters and brothers ain’t got no money. My uncles ain’t got no money… The radical organizations I support ain’t got no money. The school I went to ain’t got no money. Meanwhile, damn near everyone white around white Roger got at least some land, some inheritance, some kind of money. White Roger might be the poorest person in his family making three hundred thousand.” (147)

Roger is not a character in Laymon’s memoir. He is only the disembodied every-white man in Malachi Hunter’s attempt to convince young Laymon. As a symbol of white networks and wealth, we don’t know if what Hunter says is true about Laymon’s mother’s friend, Roger, but somehow we know that white Roger is also a common fact.

We know the phenomenon that Hunter describes by a couple of terms: the “Black-white wealth gap”, and the “Black tax.” These terms seek to describe the generational disparities between BIPOC and white Americans, disparities that obtain in academia and even at places like Colgate. For instance, has the Black-white wealth gap impacted homeownership among Black/brown faculty staff at Colgate? What does it mean to believe that our report on faculty compensation and whatever the staff equivalent is (I hope there is such a thing) somehow means that there is economic equality in our community? What are the dangers, problems, and drawbacks of operating with such assumptions? If an assumption is a position not based on proof, it seems likely that one of the reasons people make assumptions is that there is some gap in their knowledge. The Black-white wealth gap then can be understood in another way: it is a gap in how we understand and know the experiences of the diverse members of our community. I know this to be true among the noblest of us. For instance, have you ever heard statements like these: Our faculty don’t need more money; they need more time. Or, we all can afford to give x dollars…?

But what does white Roger have to do with Black Laymon’s essays; what do Roger’s generational wealth and Laymon’s generational poverty have to do with radical rhetoric at a college in the deep south? For me, Malachi Hunter is reminding Laymon that he can’t afford to take risks, even rhetorical ones, because he can’t afford to fail.

If the Black-white wealth gap moves beyond the pocket, the tiresome but true world of dollars and cents, to how one is (expansive) in the world, how one views possibilities and failures, then it also impacts the way we are perceived and how we perceive ourselves. If academe, especially at a predominantly wealthy institution, is still a kind of ivory tower where the tower-dwellers can luxuriate in learning as a liberal conceit, what happens when they actually don’t have this luxury? Is prof. white Roger more likely to speak on a hunch, to ask for what he needs, to decide what excellence is, and to have friends among the majority who understand him, and can advance him?

Mississippi is anywhere south of the Canadian border

Security is precarious when you come from the Global South. And Malcolm X was right when he quipped that “Mississippi is anywhere south of the Canadian border.”(422) Once at a table in the Merrill House, it became clear to me that people from these “souths” learn here and they work here too. Indeed for some, being employed at a predominantly wealthy institution does not ensure the financial security that many presume.