This summer, I had the great pleasure of working at the National Abolition Hall of Fame (NAHOF) in Peterboro, NY, a nonprofit organization that preserves, honors, and shares the stories of 19th-century American abolitionists. NAHOF inhabits the second floor of the Smithfield Community Center, where it hosts multiple exhibits on abolition including the hall of fame banners dedicated to its 32 inductees. Alongside its vital historical work, NAHOF also hosts events focused on local history and how we can continue the work of abolitionists today, addressing ongoing issues of inequality. I worked one-on-one with Dorothy “Dot” Willsey, the president and founder of NAHOF and its Cabinet of Freedom. Throughout my 10 weeks at NAHOF, I have truly come to cherish my relationship with Dot, and continue to appreciate all the opportunities she has provided for me.

For the majority of the 19th century, Peterboro was home to Gerrit Smith, who was a cornerstone of the 19th century abolition movement. Smith was made exuberantly wealthy by his father’s land business, which he took over at age 21. With these riches, Smith decided to make positive changes in the world, beginning with his little hamlet of Peterboro. His Peterboro mansion became a safe haven for anyone in need, no matter their class, race, gender, or relation to Gerrit. As he became more dedicated to the reform movements brewing in Upstate New York, his home soon became a heavily trafficked station of the Underground Railroad. Freedom seekers would reach his property and be met with respect, a place to stay, food, clothing, information on where to head next, safety, and kindness. Runaway slaves felt especially safe and cared for within the boundaries of Peterboro, as abolitionist Henry Highland Garnett proclaimed, “There are yet two places where slaveholders cannot come, Heaven and Peterboro.”

Additionally, Gerrit made significant donations to the abolition movement as a whole, through avenues such as his funding of Frederick Douglass’s Rochester-based antislavery newspaper The North Star and John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. It is estimated that over the course of his lifetime, Gerrit Smith gave away the equivalent of $1 billion in today’s dollars. This summer, I combed through hundreds of pages of research and writing on the life and legacy of Gerrit Smith. Yet no matter how much I read, I will never cease to be amazed by how benevolent, passionate, and giving this man was. As a wealthy white landowning man in the 19th century, he was arguably destined to turn a blind eye to the disgusting injustice and hatred coursing through America’s veins. Instead, Gerrit dedicated all of his time, money, property, and mind to aiding populations and individuals in need, all while doing what he could to humbly remain out of the spotlight.

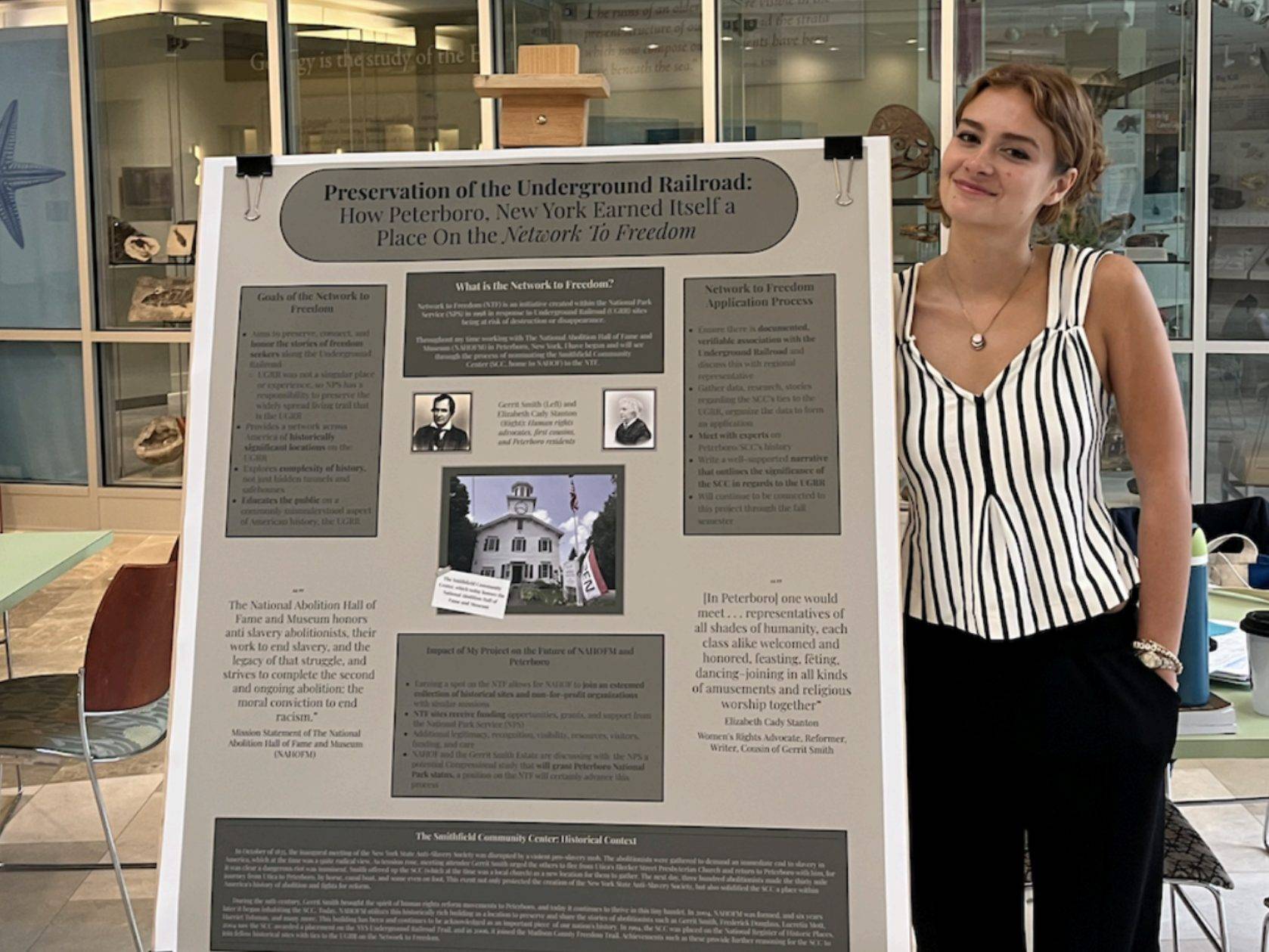

My summer project has evolved throughout the summer. When I first arrived at NAHOF, my role was to organize the seemingly endless archival research available to NAHOF so that future projects could be accomplished in a more quick and manageable way. As I began undertaking this work, we soon realized that this project was hard to define or set an endpoint for. This was part of the reason that we ended up pivoting to a different project partway through the summer. Due to my passion for history and true interest in the work being done at NAHOF, Dot and I decided that a more demanding and history-focused project would better fit both mine and NAHOF’s needs. Therefore, developing an application for the Network to Freedom on behalf of the Smithfield Community Center (home to NAHOF) became my main objective. The Network to Freedom is a National Parks service initiative created to preserve and connect sites along the Underground Railroad. Due to the late start on this aspect of my work and my continued investment in NAHOF’s mission, I will be continuing my work on this application into the fall semester. If our application ends up being approved and the Smithfield Community Center gains a spot on the Network to Freedom, NAHOF will have increased access to grant funding, networking opportunities with similar sites, and widespread awareness of the work they complete.

As summer comes to a close, I have begun to truly reflect on everything that I have experienced, learned, and witnessed throughout my summer at NAHOF. I feel indescribably grateful for the time I have gotten to spend with every person involved with the Upstate Institute and NAHOF. They have gifted me with a newfound genuine appreciation for this region of Upstate New York, and have allowed me to conduct meaningful research on its history and culture. As a history major, I feel extremely fortunate that my community partner is a history-oriented organization. I study history and educational studies at Colgate, so I believe that working at a museum has been the perfect match for me. I knew going into the summer that I would be at least slightly interested in my research, but my interest in this history has completely exceeded all of my expectations.

Additionally, as someone accustomed to metropolitan and suburban spaces, I never believed I would develop such a connection with the quiet rural nature of central New York. Yet, through my explorations for work and for pleasure, through my conversations with locals and experts alike, and through my historical research, I have truly begun to grasp just how special this part of our country is. Not only is it historically rich with the beginnings of important reform movements and filled with breathtaking landscapes, but there are always more unique areas to explore in Upstate New York. In a world so chock full of distractions, stimulation, and pure stress, there is true beauty in the quiet, small, peaceful towns of Madison County. My experience with Peterboro and NAHOF has been so enriching and enjoyable, so much so that I am looking forward to continuing my work with Dot into the fall semester! — Eliza Potter ’26